Between Interpretation and the Machines

Cultural cartography across literary studies, sociology, and LLMs

This essay traces the shifting ways scholars have tried to map culture: humanistic reading, sociological coding, statistical counting, and now LLMs. Each promises an escape from interpretation, yet each only returns us to it. If there is a path through, it lies neither inside nor outside, but between.

Every field worries about what it is really doing. Literary studies has its debates about interpretation, historical context, and the role of computational methods. Sociology has its own, often parallel, anxieties. What counts as evidence? What role does interpretation play? How far can one push formalization before the object disappears? These questions surface with particular clarity when the object of study is texts.

One fun thing about spending a little time on Substack is that you glimpse how other disciplines wrestle with similar foundational issues. I have enjoyed this in a number of areas, but since I like to read and talk about books, it is especially the case with literary criticism and literary studies. Computational approaches, sometimes called “thin reading,” have raised the question of what exactly literary scholars do, or should be doing, with particular force.

Sociology has not escaped similar uncertainties. It is worth pausing on this, because when we look across disciplines there is a tendency to imagine that the other field has settled what ours leaves unsettled, and that we can simply borrow its findings off the shelf.

In reality, the mess runs both ways. To be sure, excellent work on publishing and the “literary field” definitely exists. Clayton Childress’s work is in my opinion the best place to start, and I would highly encourage people interested in the sociology of books, reading, and publishing to check it out. But that is not my focus here. Sociology, no less than literary studies, has been beset by disputes about what it is we are actually doing when we study texts, literary or otherwise. At the center of these disputes lies the question of interpretation.

To set the stage, I’d like to give a little thumbnail, potted, and surely selective history of the sociology of culture.

For most of its early and formative period, let’s say from the turn of the century foundations up to, broadly, the late 1970s or so, sociology largely took a humanistic and interpretative approach to texts, mostly out of necessity not choice. That was the only way you could study them.

This might mean something like a (somewhat simplistic) Hegelian idea, where you take a few great texts as windows into the spirit of a culture, and access that spirit through close, intense, reading of those texts and their scholarly interpretations. It could also mean something like broad reading of many many texts across a period, recognized ones and obscure ones, to build up an account of what the broader symbolic universe of a given society or group is, and how it relates to its social conditions. At a highly general level Talcott Parsons’ books on social evolution are like this, and for a greater focus on the literary world, César Graña is a good example.

Things changed in the 1980s and early 1990s, accelerated by the dissemination of analytical technologies, especially the spreadsheet (e.g. Excel) and statistical software (e.g. SPSS and STATA).1 Of course, systematic coding of texts has a longer pedigree in content analysis going back to Lasswell and Berelson, but the spread of personal computing made such practices far more routine and accessible. These allowed sociologists to treat texts of all sorts – novels, newspaper articles, diary entries, book reviews, films, tv commercials, you name it – as data, somewhat on the model of key informants.

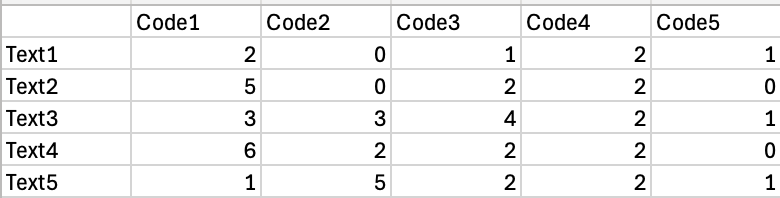

The central scholarly act changed from reading to coding, by which I mean the assignment of categories or numbers to features of texts, not coding in the programming sense. You take your dataset (of novels, newspaper articles, diary entries, etc), and create a coding scheme for it. That could be features of plot, subject matter, author, publisher, genre, whatever. There is no intrinsic limit: in principle you can assign anything you want to the object of study.

Once you have settled on your coding scheme, you then apply it. This amounts to going through the dataset, and assigning numbers to each item in the spreadsheet. You might have four categories in your coding scheme for genre (e.g. mystery, romance, thriller, detective), and then for each novel you look at, you’d give it a 1, 2, 3, or 4 (you could also do it on a continuous scale based on how closely the item comes to each category, e.g. on a 1-10 scale where a 10 is “pure” mystery, and so on). You can do the same sort of thing with newspaper articles or book reviews or author or publisher characteristics or whatever. When you are done, each item is a row, each column is a classification, and each entry is a number (or a word that could be translated into a number).

Once you have the spreadsheet in hand, the real analysis starts. This is important to keep in mind. The coding process is all background and preliminary to what comes next, which is what you would actually publish and which would take up the bulk of any article. You feed the spreadsheet into one of the aforementioned software packages, and do some statistical analysis (eventually you could also do a lot of this in Excel, but that is considered tasteless, as is SPSS). This act is what makes the research sociology. You look for correlations between characteristics of author or reader or genre, prevalence of subjects or themes across social locations and over time, and the like. Griswold’s work is a high point of this approach, and helped to define the genre.

Not coincidentally, as these tools and methods made it possible to transform text into data and reading into statistics, the sociology of culture was able to define itself as a social scientific endeavour. The sub-field came into existence as a distinct area at this time, and enjoyed remarkable growth into the mid 1990s and early 2000s.

There were many jobs in the newly created area (every department now needed a sociologist of culture), and high levels of student interest. It remains one of the largest sections in the American Sociological Association. However, new jobs are now scarce, in part for macro-disciplinary reasons, but also because the field, coming into existence almost all at once, is defined by a strong cohort effect, with its early incumbents holding onto their positions throughout their careers, and are only now nearing retirement. It will be very interesting to see if the sub-field can reproduce itself, and what it looks like as the initial cohort gives way to the next.

Separate from these issues in the sociology of the sociology of culture, the remarkable growth and success of the field papered over some serious problems with its analytical practices. Intriguingly, these only burst onto the scene with the advent of new technologies in the 2010s, give or take, namely, those that would eventually become the full and evolving suite of computational text analysis, such as topic modeling and word embeddings. This came together with the ability to digitize large corpuses of texts. STATA and SPSS also gave way in this period to R and Python.

However, the most powerful criticism of the culture of coding in the sociology of culture during this period came not from the computational side, but from the hermeneutic and interpretative one, though the former ended up joining forces with the latter. The key work was Richard Biernacki’s highly polemical (2012) Reinventing Evidence in Social Inquiry. That book advanced a number of claims, often quite aggressively, but with the benefit of hindsight it is possible to hone in on a core insight that is hard to dismiss.

Biernacki argued that the practice of coding cultural objects obscures the interpretative moment, pushing that moment essentially into the background. He showed this by doing something that, surprisingly, though perhaps not so surprisingly, nobody had done before. He asked for the original textual material upon which the coding had been done, picking famous papers and books as his targets. Surprisingly, though maybe not so surprisingly, these were very often not available, or at least they were not made available to Richard Biernacki.

A few brave authors did allow Biernacki to peer behind the curtains, and these authors truly must be credited for advancing the field. For Biernacki did not pull punches. He went through text by text and showed that nearly every coding decision of importance to what was deemed interesting in each work rested on interpretative acts that were highly contestable. It is not so much that they were wrong, but that the category of “right” or “wrong” did not apply to them in a way that would allow them to serve the evidentiary function they were being asked to perform. This is because they were after all interpretations of rich cultural objects, which admit not only of a variety of meanings, but for which any given interpretation invites another, and another, and another.

Were those interpretative processes to be brought to the surface, the entire project of those coding-based studies would be fundamentally transformed into something else. They would become humanistic interpretations, subject to the stringent strictures of that form of scholarship.

But the culture of coding was not interested in that; the action was in the statistics and correlations that could be done on the coding. It was, after all, what made it into sociology, not humanism. This lack of interest was not accidental; it sprang from the essential structure of the practice. Coding has to be in the background to do its work; it must be treated as a finished product, a fait accompli. It cannot survive the light, since as soon as it comes to the surface, it stops being what it is.

Biernacki’s own conclusion was stark. Back to Humanism! That, he argued, was the only respectable option. Few listened. Even so, while his call was not immediately widely taken up in practice, the book circulated broadly and shaped many subsequent debates. Indeed, the fact that his critique came at the dawn of computational text analysis opened another path.

A few years later, in 2015, The American Journal of Cultural Sociology published a major statement about Biernacki’s work, by Monica Lee and John Levi Martin, Coding, counting and cultural cartography, followed by a symposium about the issues Lee and Martin raised.

Lee and Martin noticed something important in Biernacki’s book. The works he criticized were, as he put it, in an

“ambiguous middle ground. None of the researchers resorted to reductive word or phrase searches, such as a computer executes. Instead, these sophisticated sociologists rejected cruder reduction and contrasted it to the more sensitive coding they sought to execute.”

For Biernacki, the “reductive word or phrase searches” were beneath contempt, and anyways were perhaps at the time rather crudely developed. Lee and Martin thought otherwise. Essentially, they fully accepted the core of Biernacki’s critique, but took it as an either/or: Either count or read. Coding is dead, but you can still count. And they saw that the new computational advances would allow counting to go much further than it had to that point.

It must be said that neither Lee nor Martin was or is against humanistic interpretation. Far from it. Monica and I co-authored several papers that were interpretations of some texts by Georg Simmel. Martin just published a massive book, The True, The Good, and the Beautiful, which is nothing other than a series of interpretations of books. John also has a terrific chapter on Simmel in a forthcoming book I am coediting, in which he interprets some under appreciated texts in connection with some basic issues in the sociology of culture and cognition.

Their central point was that, in the case of those interpretative works, the evidence is there for all to see, on the surface, as itself, and one can then responsibly evaluate and criticize it. Take Martin’s new book. While I think it is a tremendous achievement, I have some serious criticisms of not only some of the fundamental interpretations of Kant and the post-Kantian tradition guiding it, but also of many of the specific interpretations, such as of Diderot. But for every criticism, I can find the exact page where the difference lies, right there in Martin’s book, and moreover, that type of criticism is invited by a book like this; it embraces the hermeneutic circle.

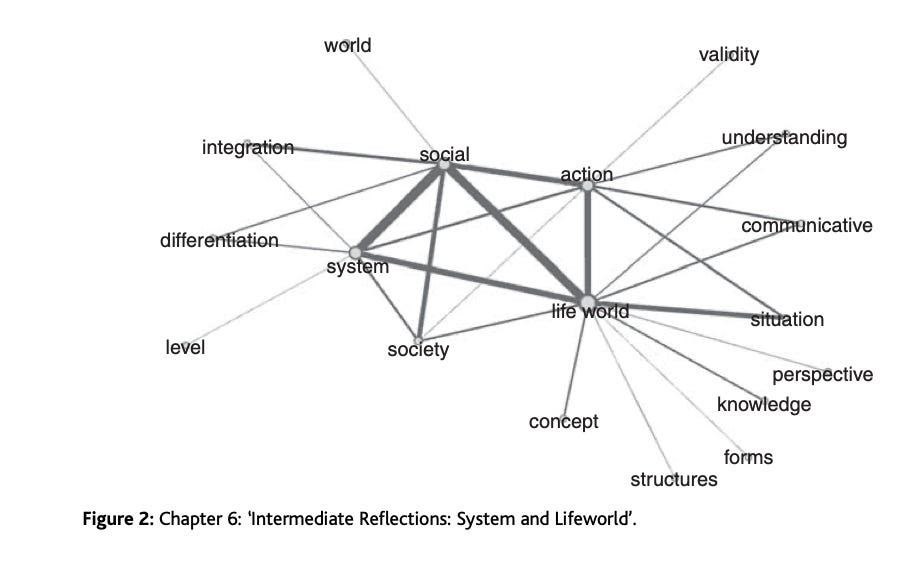

Coding, Lee and Martin argued, tries to escape that circle, and so is bound to fail. But instead of following Biernacki on a one-way street to Humanism, Lee and Martin instead argued that “his work can just as well support an argument for increased formalization as it can one for decreased formalization.” They showed this with an analysis of Frankfurt School texts, based on Lee’s dissertation.

Here is a taste of how they proceeded:

For example, let us say that we are arguing over whether Habermas or his intellectual heir, Axel Honneth, is truer to the fundamental tenets of critical theory as proposed by their common predecessors Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno. In traditional hermeneutic disputation, this is the sort of question that is very difficult to bring to closure, much to the relief of those of us who have friends or family employed in such endeavors.

What if we were to make similar maps [DS: network representations of the number of times words appear in the same paragraph], not just for…one chapter, but for the major works of Horkheimer and Adorno, of Habermas, and of Honneth? We first examine each map to make sure that it seems to have validity, in the sense of not suggesting an interpretation that goes against our general understanding of each text. Assuming we find no problems in the individual maps, we then overlay them – and now count up the degree to which, say, the graph of Habermas shares nodes and edges with that of Horkheimer and Adorno, and compare that degree with the degree to which Honneth’s graph shares nodes and edges with the earlier critical theorists. If the number indicating overlap between Habermas and Horkheimer is greater than that for the Honneth–Horkheimer overlap, we would have prima facie evidence of a declining commitment to these core values.

You will notice that this is a rudimentary version of what word embeddings would eventually supercharge, and which LLMs would super-duper charge. In this earlier context, the key issue was once again the question of how evidence becomes evident to other people. Working with text that you could count, you could make every step of your analysis evident. You can supply a file with the texts, the R or Python script, you push a button, and out pops the exact same thing.

When it comes to formal analyses, we might say that bad sociologists code, and good sociologists count. The reason is that the former disguises the interpretation and moves it backstage, while the latter delays the interpretation, and then presents the reader with the samedata on which to make an interpretation that the researcher herself uses. Even more, the precise outlines of the impoverishment procedure is explicit and easily communicated to others for their critique. And it is this fundamentally shared and open characteristic that we think is most laudable about the formal approach.

Their slogan (bad sociologists code, good sociologists count) was deliberately pointed, but it captured their view of how transparency and replicability ought to distinguish sociological practice. It is not, of course, that there is no interpretation when one does this type of “counting.” Far from it, as anybody who has done it knows. It is that, when done well, you do not disguise or black box the interpretation, but rather you delay it, and when you do make it, you make it out in the open, on a shared object that you and the reader can see between you.

To be sure, the procedures Lee and Martin discuss are and have been just as subject to the challenges of the replication crisis in the social sciences as anything else. It is in fact quite rare to just “push the button” and get the exact same thing as in most published papers. A lot of decisions are effectively black boxed. But the difference is that this all clearly falls short of the ideals built into the practice of “counting” itself, whereas, in Lee and Martin’s telling at least, the practice of coding invites it.

Not everybody agreed with Lee and Martin, and the symposium included other papers defending coding. Rather cheekily, Lee and Martin responded by applying their methods to those very papers! It is a fun little episode in the recent history of sociology that is worth the while, if you have it.

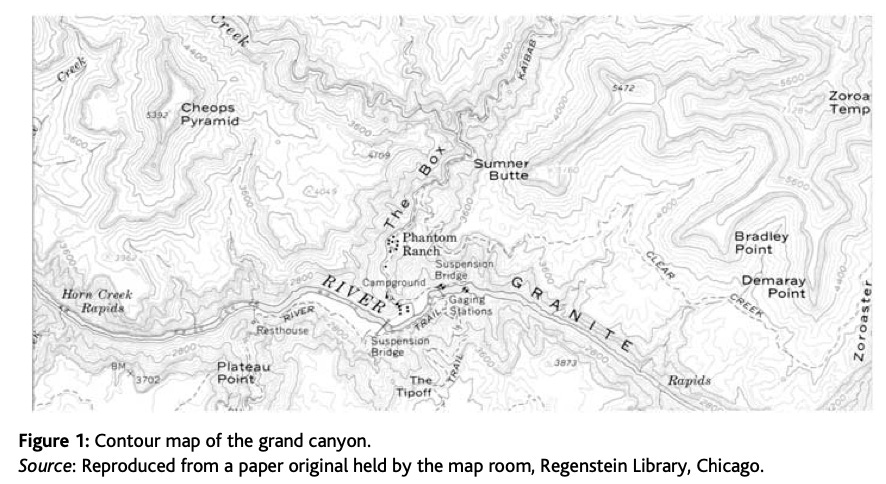

I want to close this story by noting that Lee and Martin’s title includes the phrase “cultural cartography.” This goal of mapping culture is quite similar to what an author like Leif Weatherby sees as a promise of Large Language Models (see Derek Neal’s excellent review for an overview and illustration). Yet if the history I have recounted offers any guidance, it is that the method used to draw the map is not innocent. Here, the current chatbox form of LLMs presents a serious problem.

Interacting with a proprietary model through a simple prompt is not a neutral act of information retrieval. It is, rather, an extreme form of the very practice Biernacki critiqued. The LLM acts as the ultimate coder, performing countless interpretative acts based on its training and reinforcement learning, yet it presents its output as a finished product. The entire process is a black box, pushed so far backstage that we cannot even ask to see the source material.

The parallels go further. Old-school coding meant that one researcher decided, for example, whether a passage of Habermas was “about” rationality or authority, and then that decision disappeared into a spreadsheet. LLMs do the same thing at scale. Ask for a summary of Habermas, and the model silently collapses thousands of small interpretative judgments into a few sentences. Ask it to classify a novel as realist or modernist, and it delivers an answer without disclosing the criteria by which it made that choice. Every output is built on invisible coding decisions that cannot be audited, replayed, or debated. In this sense the LLM is not just like the coder, it is the coder, only multiplied and hidden behind a screen of fluency.

The alternative is not to abandon these powerful tools, but to subject them to the principles that Lee and Martin championed for “counting.” This means favoring methods that preserve transparency and allow interpretation to be delayed. We can, for instance, still use techniques like word embeddings on our own curated corpora, where we control the process and make the method of data reduction explicit. It also means engaging with open-source models where the architecture and weights are available for scrutiny, or using platforms (such as

’ Chatstorm!) that are built for reproducible analysis and experimentation.The lesson of the long struggle over reading, coding, and counting is that the integrity of our claims about culture depends on making our evidence evident. Whether the tool is a spreadsheet or a transformer model, the challenge remains: to create a shared object that we and our readers can analyze together, out in the open. The temptation is always to find an exit from the hermeneutic circle, either by retreating inside into pure interpretation or stepping outside into the machine.

The only path to validity, though, is in between: in making and defending claims for others to judge.

Randall Collins has persuasively argued that rapid movement in a field is usually driven by new technologies of observation.

Brilliant as always! I love the count vs code distinction, though I wonder how much LLMs complicate that. Model training has "counted" a vast possibility space and a chat UI paradigm can't help but "code" that dimensionality into a discrete path based on little more than prompts and probabilities.

The problem is that we have so few paradigms for high dimensional UIs that could honor that distinction. E.g. imagine a UI that shows a Habermas path forking into semantic "neighborhoods" of rationality and authority. The size and smoothness of the diverging paths could reflect their probabilistic weights. I might choose to chat in the rationality neighborhood for a while, or have multiple agents explore both to analyze what converges. So many possibilities..

Really appreciate how you traced and presented this debate. I ran into this ‘black boxing of interpretation’ when engaging with the ‘Culture and Cognition’ literature. For example, I read a paper that claimed that someone’s thought was less coherent than another’s, based on some dispersion measure. It was also by encountering this issue that I started to think more deeply about the social triangulation of meaning and how that might play out. Looking forward to JL Martin’s Simmel chapter!