I recently finished Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate. I hadn’t heard of this book until relatively recently, when I saw it being discussed as one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, maybe even of all time.

This I found somewhat strange. I had thought that as a graduate of the Committee on Social Thought, Great Books were in my wheelhouse. If I haven’t read them all yet (to my shame), they should at least all be on my radar. New ones don’t come around very often.

So of course I read it. I would say that for the first three to four hundred pages, maybe a bit more even, I didn’t quite get the hype (it is about 900 pages). It seemed like a book that wanted to be a Great Book, but didn’t quite have it. Then somehow it clicked, and I was sold.

I am not sure exactly where it happened, but by the time I got to the scene with Sofya holding David’s hand on the way to the gas chamber, I knew I was having an encounter with one of those truly rare product of the human imagination. An all-timer. It belongs on any Fundamentals Exam list, without question (I do not think it was on any during my time at CST, but I could be wrong).

One way to index the changes in my experience of the book was my changing appreciation of the title. For some time in my reading, I understood Life and Fate to be a kind of wannabe Crime and Punishment or War and Peace. Not only in the sense of mimicking the genre form of two Big Words joined by “and.” It was that the “and” (I thought) was not really an “and.” It was more of an “or.”

The book seemed to present us with a choice: life or fate. Do you want to live your life, your individual life. Or will you submit to your fate, as a Jew, as a Bolshevik, as a soldier, as a wife, as a husband, as a scientist. Whatever it is, there is life, individual life, and on the other, some force that has the potential to crush the individual.

This is an important idea, don’t get me wrong. But it is not exactly original. Nor is it exactly like the “and” in Crime and Punishment or War and Peace. In those, the “and” tells us that two ideas that we thought were distinct are in fact part of one and the same process. Crime is internally related to punishment. War is internally related to peace. How is that possible? What could that mean? That is in part what makes these books Great. But if it is Life or Fate, that is not so interesting.

It is when I realized that no, in fact, the “and” in Life and Fate has the full force of the word “and” that the book upshifted for me. It is showing us that Life is internally related to Fate, Fate is internally related to Life. What does that mean? How is that possible? That “and” is much more interesting than the “or,” which is probably why Grossman did not in fact call it Life or Fate.

Georg Simmel’s “The Problem of Fate”

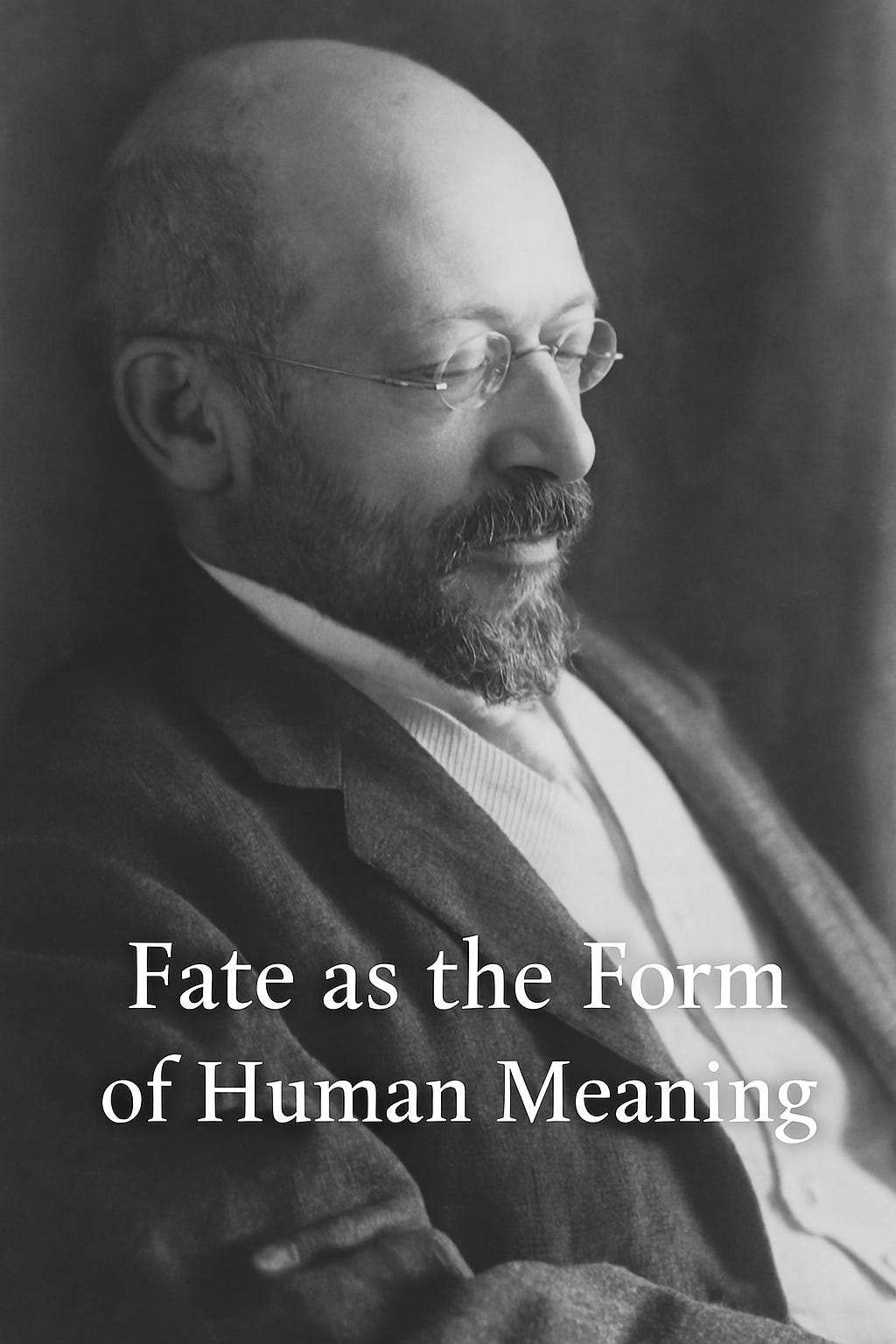

Below I highlight a few scenes where the power of the “and” comes into view. But I want to first step back and draw a connection to one of my favorite social theorists, Georg Simmel. That might seem surprising, since Life and Fate seem like such philosophical themes. But Simmel was in fact first and foremost a philosopher, both in his own mind, and mostly in the mind of his contemporaries (Heidegger for example attended his lectures on the meaning of death, and “creatively appropriated” many of those ideas).

This was true throughout his career, but in his later years, Simmel made it his mission to articulate the metaphysical “view of life” that coursed through all his work, including his sociology. You can see some of my own efforts to explicate how here, here, here, here, here, and here. Sociologists are only beginning to appreciate this aspect of Simmel’s career (stay tuned for me and Milos’ forthcoming Handbook on Simmel, which includes some fascinating new essays by scholars working in this direction).

And as it happens, Simmel’s final work, The View of Life, contains a section drawn from an earlier essay, called “The Problem of Fate.” The book is an entry in the philosophy of life, which contains an analysis of the problem of fate. It puts together Life and Fate. I’d like to suggest that it helps us to understand what Grossman is showing us in his novel.

We can distill from Simmel’s essay a few key insights relevant for understanding the “and” in Grossman’s title. First, Simmel notes that modern philosophy – and sociology for that matter – has tended to neglect topics with great existential significance but which tend to be experienced as somehow contingent and passive, or at any rate not under our direct active control. Simmel mentions love in this context, but we can also speak of more mundane phenomena such as laughter and crying. These are crucial parts of our experience. We organize our lives around them, sometimes even seeking to increase their likelihood of occurring. But we cannot directly, actively, will them. If you are choosing to laugh, then you aren’t really laughing; nor can you really choose to cry, or fall in love, or asleep.

The larger goal of Simmel’s own late philosophy is to articulate an alternative, vitalist metaphysics in which concepts like fate could have a natural place. Setting aside that larger goal for now, what he has to say about life and fate is interesting in its own right. The basic structure of fate in his view involves a kind of synthesis of inner and outer. It is not a property of the event itself. There are no “fateful” happenings, pure and simple.

Rather, fatefulness arises in the relation between some event and the inner determination of a person as the person they are or are becoming. More specifically, Simmel envisions 1) a person with an inward sense of purpose or direction; 2) an external event, initially unrelated to this purpose, that intervenes and disrupts it; and then 3) a reinterpretation of this event as deeply significant in light of that purpose, potentially altering the purpose itself.

These three align when they cross a “threshold” of fate, Simmel claims. Many occurrences are not experienced as fateful. But sometimes, even minor events come to alter the course of a person’s life, such as a chance encounter that somehow redirects your energies or activities. Fate is not merely what happens to us. It is the convergence of external fact and internal meaning in the form of an individual life.

There is another sense in which fate represents a kind of threshold experience. Simmel sees fate as a human boundary concept. Neither God nor animal can experience fate. God’s thought is already action, there is no limitation or resistance, which is to say, no passion. God thinks, and bam, it happens. In fact, there is not enough space between thought and action for any “bam” to fit between them. For animals,

“there is only life itself…which, can be supported or restrained as it takes its natural course. More or less in contrast to human life, however, animal life does not entail the idea of a special course which is realized or disturbed by reality.”

Humans, by contrast, exist between these upper and lower bounds. Sub-fateful experience is the domain of passive puppets of external events. Supra-fateful is the domain of god-like autonomy. Humanity in Simmel’s view exists between these boundaries and is marked by the strange capacity to imagine life beyond that threshold, as a fall into animality or a pretension to divinity.

The capacity to have a fate depends on us having some capacity for self-determination, some vulnerability to the external causal order, and some capacity to transmute that externality into the determination of the self. This tripartite structure is what gives fate its tragic quality.

The tragic hero meets his destruction in the friction between all kinds of external conditions and his own life’s intention, which marks out beforehand in a fundamental way that this alone is going to occur. Otherwise, his downfall would not be tragic but merely sad…For this reason, the significance of the concept of fate – namely, that objectivity in its character as mere event may be transformed into the meaningfulness of an individual teleology of life or be revealed as such –…never entirely relinquishes its independently causal and alien nature.

Tragedy expresses the “residual otherness” of fate in the collision of a character with some external necessity. While retaining the full force of its externality – events hit the tragic hero, he does not choose them – this necessity somehow completes or realizes that very character.

Becoming Sofya Levinton

Now let’s return to Grossman, and pick out a few scenes to think about this idea of the role of fatefulness in human life.

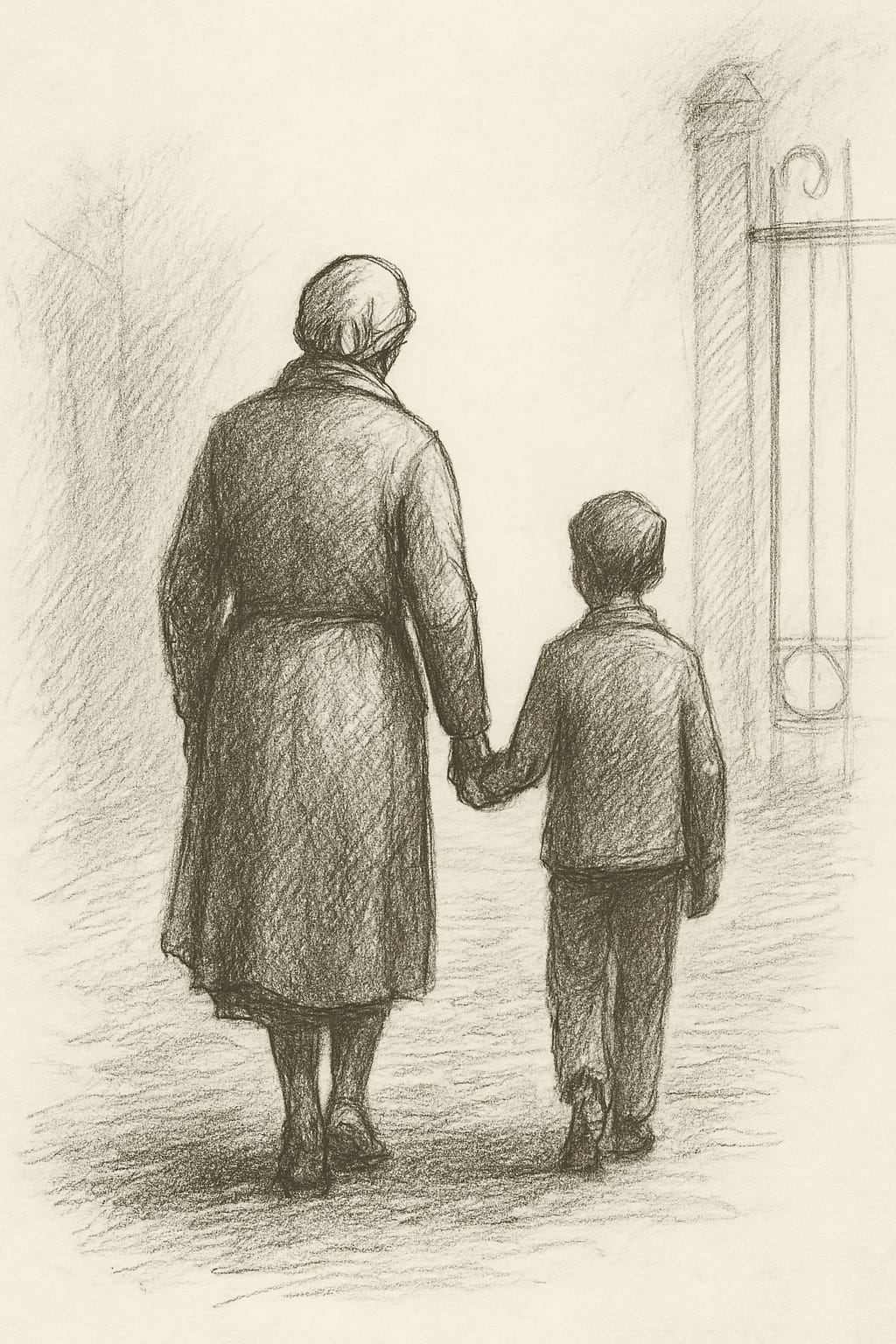

Consider first Sofya Levinton. She is a Jewish pediatrician who was arrested during the Holocaust and sent to a Nazi extermination camp. On the train, she forms a deep bond with a young boy named David, who had lost his mother. At the camp, the Germans offered those Jews with some medical expertise the chance to save themselves. Sofya refuses. Instead, she chooses to stay with David and to accompany him into the gas chamber. Their walk into the chamber is the center of perhaps the most gripping and eerily humane scene in the entire novel.

How do life and fate fold into one another in the person of Sofya Levinton? In part it is the arbitrary fact that she is a Jew, at that place, at that moment in history. But that is not yet fate, in Simmel’s sense. Those are occurrences or events.

Things get closer to the threshold of fate when she connects with David on the train. But this is still not yet fate. She can choose to extricate herself from that relationship whenever she wants. After all, David is not her son, and we watch throughout the journey as prior obligations and commitments are stripped away from many of the Jews, and along with them, their humanity.

The truly fateful moment comes when she has the chance to extricate herself from the march into the gas chamber, by letting the Germans know her medical training. Once she refuses that escape, her fate is sealed.

That moment transforms an occurrence into a determination of who she is. It becomes her. She becomes it. At that same moment, Grossman’s narration correspondingly transforms. The prose slows. It becomes intimate yet elevated, somehow at once completely from within her and David’s inner experience but also watching it all unfold from above.

The door to the gas chamber opened gradually and yet suddenly. The stream of people flowed through. An old couple, who had lived together for fifty years and had been separated in the changing-room, were again walking side by side; the machinist’s wife was carrying her baby, now awake; a mother and son looked over everyone’s heads, scrutinizing not space but time. Sofya Levinton caught a glimpse of the doctor’s face; right beside her she saw Musya Borisovna’s kind eyes, then the horror-filled gaze of Rebekka Bukhman. There was Lusya Shterental – nothing could lessen the beauty of her young eyes, her nose, her neck, her half-open mouth; and there was old Lapidus walking beside her with his wrinkled blue lips. Again, Sofya Levinton hugged David’s shoulders. Never before had she felt such tenderness for people.

It is as if Sofya the human organism became Sofya Levinton, a person of character, in making that event into something more than a mere event. She responds, or better to say Grossman responds, by turning her life into something with determinate meaning, all the way to the end.

Her eyes – which had read Homer, Izvestia, Huckleberry Finn and Mayne Reid, that had looked at good people and bad people, that had seen the geese in the green meadows of Kursk, the stars above the observatory at Pulkovo, the glitter of surgical steel, the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, tomatoes and turnips in the bins at market, the blue water of Issyk-Kul – her eyes were no longer of any use to her. If someone had blinded her, she would have felt no sense of loss.

The uncanny eeriness of this description could be the apex of that tragic aspect of fate Simmel articulated. Like Oedipus, her eyes become useless, so much so that she does not even need to blind herself.

None of this is to say that anybody would choose or want this. Of course not! But that is just the point. Sofya could not and did not choose any of this. It is her fate, and whatever she did in response, would inevitably reveal her character. Her life was her fate.

Becoming Viktor Shtrum

Sofya’s fate has a kind of tragic nobility to it. Viktor Shtrum’s is different. When his fateful moment arrives, his life reveals itself to be one of self-contempt.

Viktor is a brilliant Russian Jewish physicist, who devotes his entire life to science, even as all else is crumbling around him. His mother was trapped in a Nazi-occupied area and killed, which Viktor only learns of through a letter. Upon receiving it, he is left wracked by guilt. His colleagues will not accept his theories, and he faces increasing suspicion due to antisemitic purges and ideologically imposed orthodoxy. In the face of all this, he comforts himself with the thought of the nobility of science and his own dedication to the truth, regardless of any external pressure. He seems ready to make this his fate.

And yet, you cannot simply choose what event will determine your fate. The threshold event comes from outside.

Standing on the verge of professional and personal ruin, Viktor unexpectedly receives a phone call from Stalin. Very few words are exchanged, but Stalin wishes Viktor success in his work on nuclear physics. This is all it takes to totally transform Viktor’s life. He need not even tell anybody else about the call; news of it will find its way everywhere that matters. This event crossed the threshold; however Viktor responds to it will determine who he is.

In the event, Viktor becomes somebody he wishes he was not. In one revealing moment, Viktor reminisces about his earlier readiness to sacrifice himself to science. It seems naïve after the call from Stalin. It was not a matter of fate.

That call was Viktor’s fateful moment, and soon enough, Viktor compromises his integrity. He denounces colleagues who have been purged and signs a letter condemning an innocent man.

Who else had signed the letter? Chepyzhin? Ioffe had, but Krylov? And Mandelstam? He wanted to hide behind someone’s back. But it had been impossible for him to refuse. It would have been suicide. Nonsense, he could easily have refused. No, he had done the right thing. But then, no one had threatened him. It would have been all right if he had signed out of a feeling of animal fear. But he hadn’t signed out of fear. He had signed out of an obscure, almost nauseous, feeling of submissiveness.

We can think of this as an instance of the “On the Waterfront” principle. Viktor could have been a contender, but his fate was to be a bum. Not just a bum, but a bum that could have been a contender. Viktor does not make this fate his own, not in the way Sofya does. Instead, the external meaning, state recognition, rushes in to fill the space where his own could have been. That becomes his fate: to live with the meaning he failed to claim for himself. That is the fate of a life doomed to self-contempt.

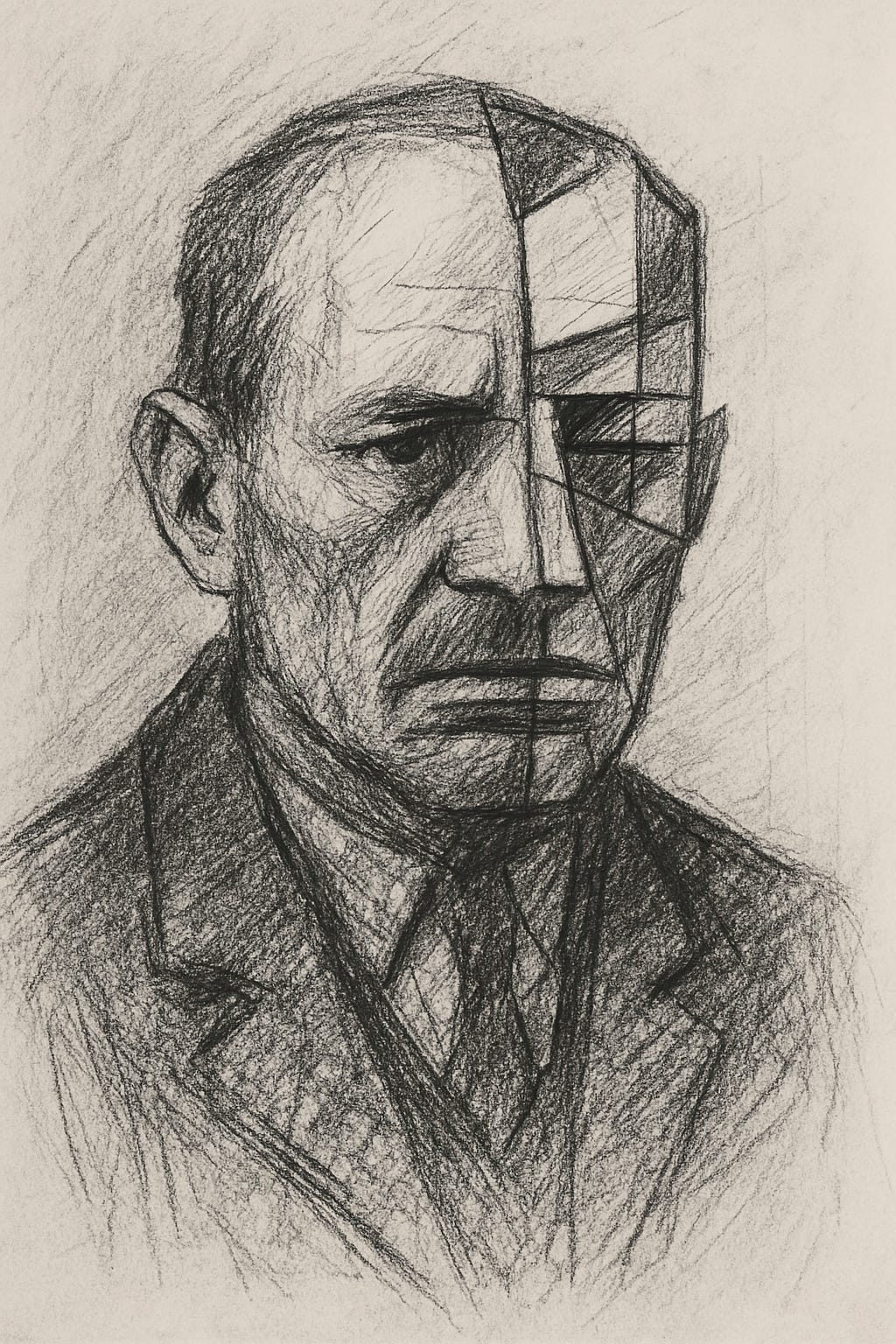

Becoming Nikolai Krymov

Sofya and Viktor in their own ways show the subjective side of life and fate. One appropriates fate as a determination of her own character. The other does not, and has to live with the fact that fate determines his character regardless. Nikolai Krymov takes us to another of the Simmelian insights into fate, about how fate is at least one marker of the border between animal creature and human animal.

Krymov is an Old Bolshevik, a committed Party intellectual, and a political commissar. At the start, Krymov believes in the righteousness of Soviet socialism and sees himself as a servant of history. But after being arrested on vague charges, he is interrogated and imprisoned by the very system he once upheld. Stripped of status and power, he confronts his past relationships and betrayals, including his failed marriage and his earlier denunciations of comrades.

The pinnacle of Krymov’s story comes in a detention center, where he is interrogated by a Soviet officer, whose job it is to get Krymov to confess to political crimes he did not commit. The scene is likely modeled on Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor. It is, along with the Sofya-David scene, probably the most singularly stand-alone pieces of brilliant writing in the book.

I only want to highlight how it deepens the meaning of the “and” in Life and Fate, considering Simmel’s insights in The Problem of Fate. From that point of view, Krymov’s fate was sealed at this moment:

‘Hand over your weapon and your personal documents.’ Krymov’s reply was confused and meaningless. ‘But what right . . . ? Show me your own documents first . . .!’ There could be no doubt about what had happened – absurd and senseless though it might be. Krymov came out with the words that had been muttered before by many thousands of people in similar circumstances: ‘It’s crazy. I don’t understand. It must be a misunderstanding.’ These words were no longer those of a free man.

What does it mean to have been a free man and to cease to be so? That is Krymov’s encounter with fate.

‘So that’s what happened,’ said the investigator. His face became human again. He closed the file, but without tying up the curling tapes.

‘Like a shoe with the laces undone,’ thought the creature with no buttons on his trousers.

“The creature” is what Krymov has become. He is no longer fully human, but not fully animal either, more like a hollowed form that dimly recalls what it meant to have had a self. As if in correspondence, the investigator at this same moment takes on almost god-like ability to shape shift.

But how evil he looked now. His very ordinary face – since 1937 Krymov had seen many such faces in raykoms, obkoms, district police stations, libraries and publishing houses – suddenly lost its ordinariness. He seemed to be made up of distinct cubes that had yet to be gathered into the unity of a human being. His eyes were on one cube, his slow hands on another; his mouth that kept opening to ask questions was on a third. Sometimes the cubes got mixed up and out of proportion. His mouth became vast, his eyes were set in his wrinkled forehead and his forehead was in the place that should have been occupied by his chin.

But the investigator’s truly god-like power is to utter “so that’s what happened,” and through that utterance to make it so. That is the image of divinity, to determine, though words alone, what happened.

But the interrogator is no god. Krymov and the investigator are seeing each other through the looking glass of the problem of fate. Krymov is not a mere creature, he is a person who has descended into animality; the interrogator is no god, he is what a fallen person sees as he looks at himself from beneath his humanity. Looking out from the side of a person falling into the sub-fateful, Krymov sees a twisted and distorted image of the supra-fateful on the other end.

In Grossman’s depiction, Krymov represents perhaps one of the most terrifying potentials of totalitarian power: not merely coercion, but the internal restructuring of subjectivity, where the victim’s need for coherence is redirected toward the very source of their destruction. In Simmelian terms, Krymov slips beneath the bounds where fate can still be made one’s own, where the self loses the capacity to determine meaning, and instead reconciles to pure external causality. The interrogator becomes not just his captor, but a twisted mirror of his lost determination, the god that makes him into a creature with a memory of being something else.

Before then, though, Simmel might say Krymov teeters on the threshold, and that is the drama of these scenes. Can he integrate this breakdown into a new, inner structure of meaning? Or does he allow his fate to be a life beneath fate? That is perhaps the most powerful aspect of Krymov’s story from the point of view of how life and fate intersect. It is where Grossman’s writing is able to hold open the threshold experience between life and fate for as long as possible and show us what it is like to be at the limit point between the two.

A fateful smile

Those three moments are clearly among the peaks of the novel, but I want to also consider two others that are a bit more subtle. The first is a German soldier, Private Schmidt. He story is brief. He is among German prisoners who at the end of the Battle of Stalingrad are taken prisoner. For some reason, he cannot resist smiling.

The prisoners tried to look straight ahead – as a sign that even their gaze was now captive. Private Schmidt was the only exception: he had smiled as he came out into the daylight and then looked up and down the Russian ranks as though he were sure of glimpsing a familiar face.

This smile enrages the Russian officer.

Just then Filimonov caught sight of Schmidt’s large, smiling face and shouted: ‘So it makes you laugh, does it, to know that another of our men’s been crippled? I’ll teach you, you swine!’

Schmidt is then shot. I found the description to be somehow totally uncanny.

Schmidt was unable to understand why his well-meaning smile should have made this Russian officer scream at him with such fury. Then he heard a pistol shot, seemingly quite unconnected with these shouts. No longer understanding anything at all, he stumbled and fell beneath the feet of the soldiers behind. His body was dragged out of the way; it lay there on one side while the other soldiers marched past. After that, a group of young boys, who were certainly not afraid of a mere corpse, climbed down into the bunkers and began probing about under the plank-beds.

Take a look at the writing here. It starts out from inside Schmidt’s point of view, telling us what he sees and hears. He hears a shot. In the course of the next sentences, his understanding of “anything at all” disappears, he stumbles, and falls. Through that clause, the writing moves from inside to out, and now “his body was dragged out of the way.”

That transition from agent to object is so subtle and smooth that you can miss it, but it was a crossing into objecthood. He had passed from subject to item, from man to remains. The gas chamber scene also achieves this kind of inside-becoming-outside effect, but here it is again, in a smaller scene that can easily pass you by.

You could read the Private Schmidt scene as showing how rank and file life lives beneath the threshold of fate. He is an item, not a subject, immediately converted into an object, without having the chance to make his fate meaningful. This might be correct.

Still, I do think there is something significant in the fact that Grossman emphasizes his smile and laughter. Recall that laughter is one of those phenomena that is at once deeply human and yet also involuntary. It shows the limits of voluntary choice in defining human character.

The smile was perhaps contemptible to the Russian officer because it meant that Schmidt was not yet fully captive. Schmidt was moved by something else, which meant he was not acknowledging the seriousness and authority which the situation should have had. There is a source of meaning that the officer does not control. Precisely because smiling and laughing have an involuntary quality, they make Private Schmidt into a kind of existential provocation: not a conscious enemy combatant, but a human being who momentarily escapes the officer's total power. And that sealed Schmidt’s fate.

Life After Fate

What that also did is make Schmidt worthy of including in the novel by name. The last chapter of the entire book is remarkable in that all names disappear. It describes the slow return to ordinary life after the war. A woman sits in her room sewing, a child plays, a soldier sleeps, there is talk of spring.

Early next morning, before the little girl had woken up, the tenant and her husband set off for the next village. There they’d be able to buy some white bread with his army ration-card.

The officer felt as though his throat, which had been scorched by frost and vodka, which had been blackened by tobacco, dust, fumes and swear- words, had suddenly been rinsed clean by this blue light.

They walked on in silence. They were together – and that was enough to make everything round about seem beautiful. And it was spring.

Nobody has a name, all are described in terms of generic roles. This is what life is like after fate. The great events have passed, and people slip back into their anonymous rhythms. They live lives of peace and tranquility, or at least with the hope thereof, and that is good.

The anonymity tells us something about Grossman’s vision in and of Life and Fate. They will only acquire a name, or at least be worthy of a name, when fate calls. At that point, they, and we, find out who they, and we, really are.

Until then, what remains is life after fate.