This little fictional lark is a companion to The Attention Economy Never Existed. If you haven’t read that yet, check it out, and the come back here to come along with me down some of the strange thought paths I sometimes can’t help to follow much farther than I probably should.

Here we start from Michael Goldhaber’s essay, “The Attention Economy and the Net,” which has become one of the founding documents of the Attention Age. In that lecture, Goldhaber uses his own lecture as an image of what an attention economy is like:

You are reading this paper, or more likely, since it is intended to be delivered at a conference, listening to me speaking it. You have a certain stock of attention at your disposal, and right now, a large proportion of the stock available to you is going to me, or to my words. Note that if I am standing in front of you it is difficult to distinguish between paying attention to me and paying attention to my words or thoughts; you can hardly do one without doing the other. If you are just reading this, assuming it gets printed in a book, the fact that your attention is going to me and not just to what I write may be slightly less obvious. So it is convenient to think of being in the audience at this conference in order to consider what attention economics is all about.

First of all, if this talk is not a total bust, at this moment I am getting attention from a considerable audience. There is a net flow of attention towards me. If this is a reasonably polite group, there may be no great competition for your attention at the moment, but nonetheless, if there were, you would have to choose, or someone else, say the chair, would. The assembled audience cannot really pay attention to very many people speaking at once, usually not to more than one, in fact. Which is another way to say that the scarcity of attention is real and limiting.

Now this might not matter if attention were not desirable and valuable in itself, but it is. In fact, it is a very nice feeling to have respectful attention from everybody within earshot, no matter how many people that may include. We have a word to describe a very attentive audience, and that word is "enthralled." A thrall is basically a slave. If, for instance, I should take it in my head to mention panda bears, you who are paying attention are forced to think "panda bears," a thought you had no inkling would come up when you decided to listen to this talk. Now let me ask, how many of you, on hearing the word "panda" saw a glimpse of a panda in your imagination? Raise your hands, please. Thank you. ... A ha.

What just happened? I had your attention and I was able to convert it into a physical action on some of your parts, raising your hands. It comes with the territory. That is part of the power that goes with having attention, a point I will have reason to return to. Right now, it should be evident that having your attention means that I have the power to bend your minds and your bodies to my will, within limits that in turn have to do with how good I am at enthralling you. This can be a remarkable power. When you have superb control over your own body, so that you can perform great athletic feats, it feels great; likewise, it feels good when your mind feels focused and powerful; how much more wonderful then to be able to have the minds and bodies of others at your disposal! On the rather rare occasions when I have felt I was holding an audience "in the palm of my hand, hanging on my every word," I have very much enjoyed the feeling, and of course others who have felt the same have reported their feelings in the same terms. The elation is independent of what you happen to be talking about, even if it is to decry something you think is horrible.

What I find fascinating about this image is how far it is from what the digital systems that actually constitute the “attention economy” actually do. It envisions attention as a kind of mystical psychological substance that flows from audience to speaker, giving the latter some sort of ability to pull the strings of the former. To see how much this covers over the actual dynamics of social media platforms, and to see why “the attention economy” never existed but instead we now live under social capitalism and the era of clout in which influence is the central claim token, let us reimagine Goldhaber’s scene anew:

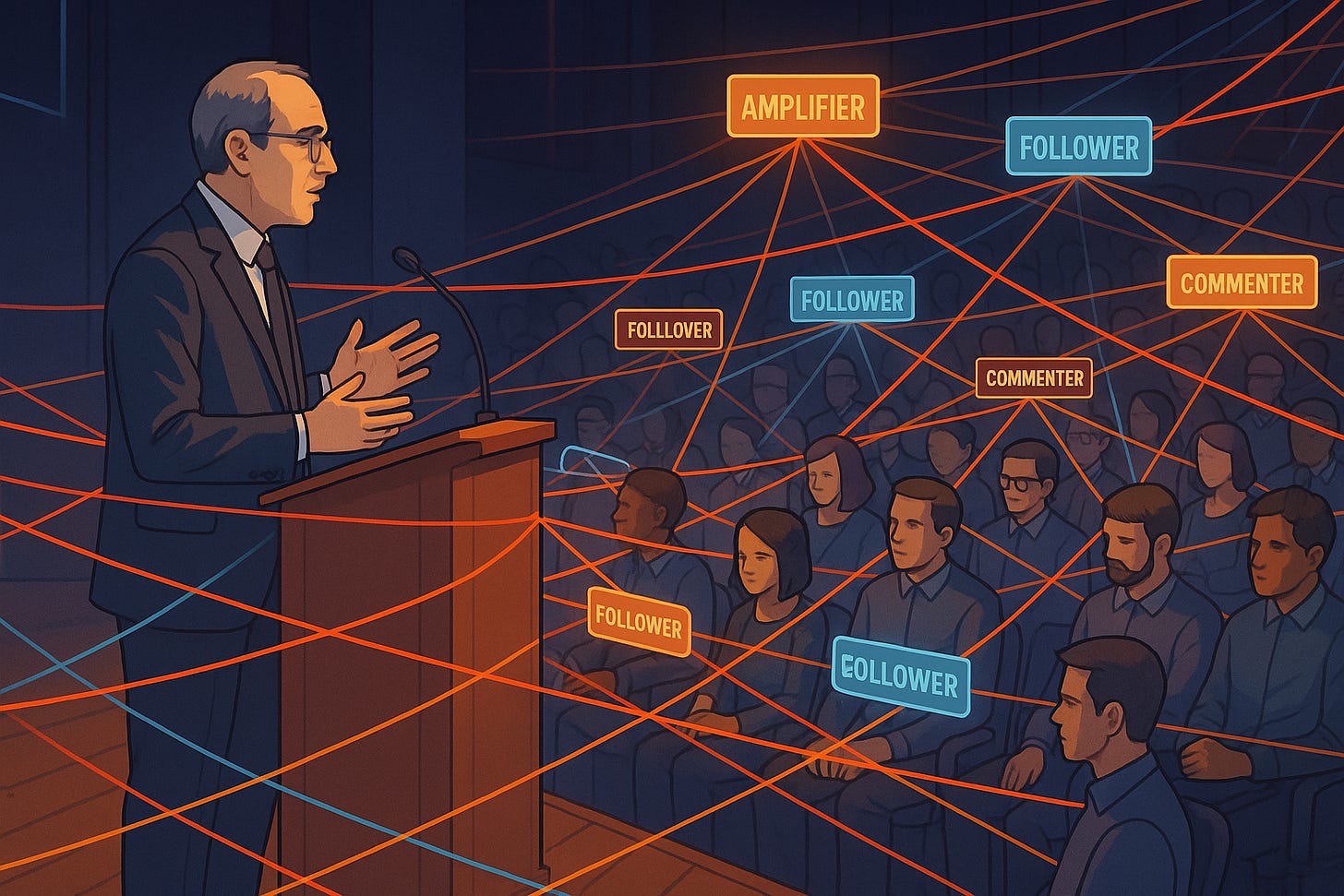

There he is, standing at the front of the room, giving his talk. As he speaks, every attendee is given a placard that displays their current status in relation to him and to one another. Some placards read "Follower," others "Sharer," and a select few might have prestigious titles like "Influencer" or "Aggregator." Each placard updates dynamically based on how the individual engages. Each attendee actively “earns” these designations by performing certain actions, such as giving Goldhaber their sustained attention, nodding in agreement, or signaling interest by taking notes. In real time, the placards change to display these new designations.

Then, strings are introduced. When an attendee’s engagement crosses a certain threshold, a red string is tied from their placard to Goldhaber’s, symbolizing a "commitment" granting him influence, visible to everyone else in the room. These strings can represent degrees of influence: a thin, fragile string for casual attention, a thicker, reinforced cord for devoted followers, and a bright, golden thread for those who repost or amplify his message outside the room. Strings do not just connect the individual to Goldhaber; they interconnect with other strings between attendees.

As attendees interact, new connections and rules kick in. Suppose one attendee turns to their neighbor and whispers about how interesting Goldhaber’s points are. A blue string is extended from that neighbor’s placard back to Goldhaber’s, representing indirect influence. Another attendee posts their thoughts on a bulletin board at the back of the room, which allows others to "share" and "like" the comment, represented by yet more strings branching off from the bulletin board to both Goldhaber and the original poster. These shared strings reinforce the influence web in increasingly complex patterns, creating a visible, physical network of interdependencies.

The room itself becomes a webbed scene, with an array of rules codified on signs hung on the walls. "Golden strings signal amplification,"* one rule reads, meaning that certain levels of influence grant Goldhaber’s original message a wider reach beyond the lecture room itself. Another placard says, "Attendee status updates every 10 minutes," reminding everyone that influence is continually recalibrated based on ongoing interactions.

Now, imagine a rule that attendees with thick enough strings connecting them to Goldhaber are obligated to share their learnings with a specified number of people outside the lecture. This obligation is displayed prominently on their placard, and at the end of the lecture, they have to record the names of people they’ll share the information with. Failure to do so means their influence rating drops in the next gathering, a penalty displayed by cutting some of their strings or shrinking their placard designations.

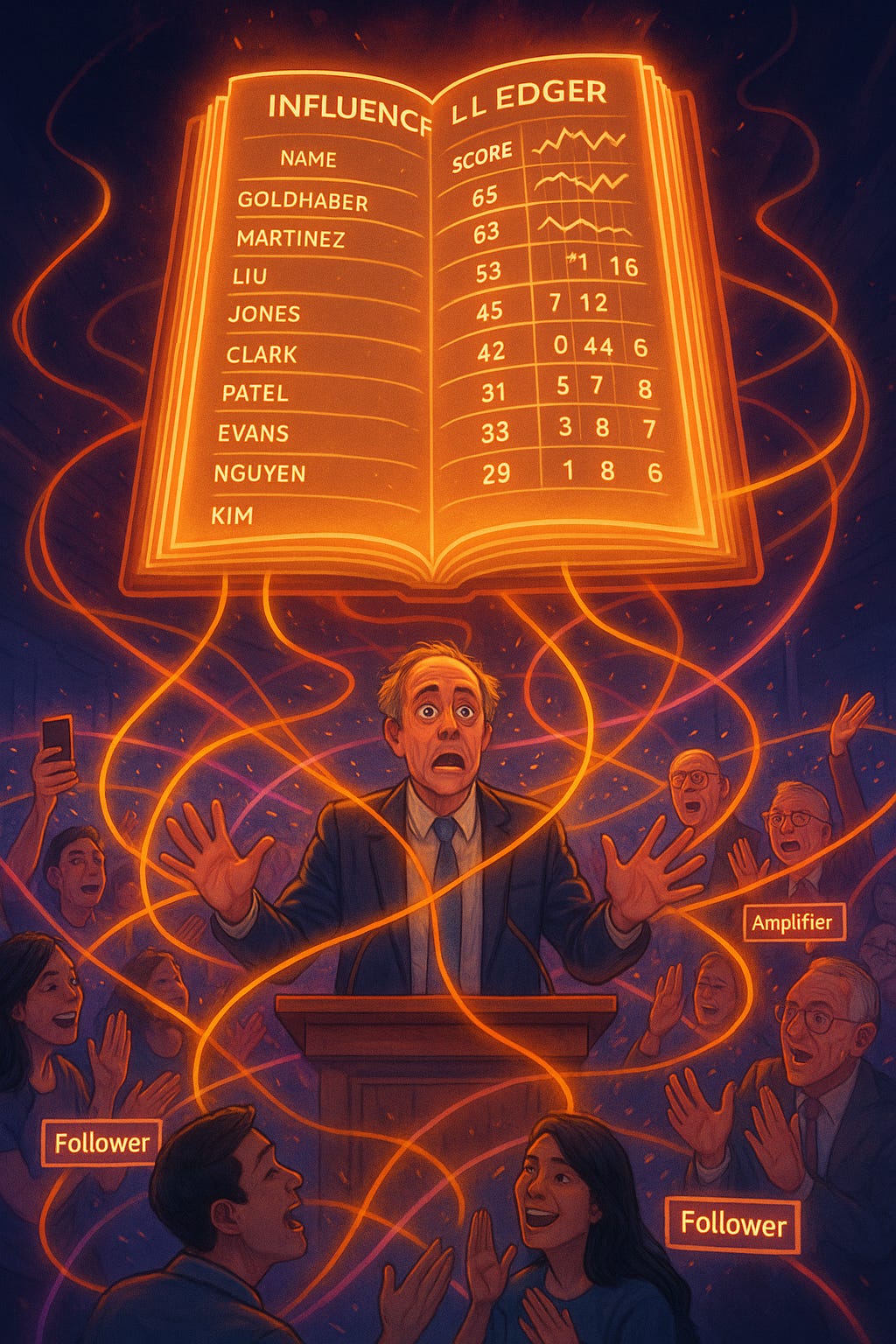

Now officials begin moving through the crowd, ensuring compliance with the rules and string placements, occasionally reassigning placards or adding new strings based on attendees’ behaviors. As the lecture progresses, each person’s engagement generates tangible influence tokens: small, physical tokens handed out by the officials, stationed around the room. These tokens are collected based on actions of others: listening intently, making a visible show of agreement, whispering praise to neighbors, or posting on the bulletin board. Goldhaber himself has a unique token, which represents his “content creator” status, granting him a baseline influence value that is always higher than anyone else's initial value. However, this originator token has strings attached. He must keep providing valuable input (the lecture itself) to maintain his originator status, lest it diminish.

Each attendee’s placard now shows not only their status, but also a numerical influence score, which fluctuates throughout the lecture. If someone whispers about Goldhaber’s key point to their neighbor, both people earn tokens, and their influence scores rise.

More participant types enter the scene. Some individuals are designated as “Commenters,” who gain influence by offering reactions to Goldhaber’s ideas, either by responding on the bulletin board or making statements out loud. Commenters now have unique tokens representing their influence as secondary amplifiers, tied not only to their direct engagement with Goldhaber but to how many other attendees respond to or build upon their comments. If a commenter raises a valuable point that sparks a chain of additional comments, the officials quickly distribute more tokens to that commenter, boosting their score and marking them as a significant influence node.

Commenters can also lose tokens if their points don’t resonate. However, the commentariat, as they come to be known, always remain structurally dependent on Goldhaber. They never gain as much influence as he does, and depend on him to provide them something to comment on.

Goldhaber himself becomes part of this structured web of influence. While his originator token offers him prestige, he can only keep it by earning “feedback credits” -- engagement from attendees that confirms they are still paying attention and finding his insights valuable. If he notices that an attendee’s influence score is rising rapidly through frequent commentary or dynamic interactions, he may, for instance, decide to engage directly with that person’s ideas. Doing so creates a thick golden thread between him and that attendee, granting them direct visibility and elevating them as a “Trusted Amplifier.” This status is now displayed on their placard, along with the expectation that they’ll contribute significant ideas or reflections throughout the event.

A new rule is introduced for everyone in the room: once someone reaches a certain influence threshold, they are obligated to contribute publicly, either by summarizing a key point or offering a unique perspective. This obligation serves as an enforceable right for everyone else: they now have the right to expect valuable input from this high-ranking attendee, whose score has elevated them to a semi-official influencer status. If the person fails to fulfill this role, they lose tokens, and their influence score drops in real-time, just as users who gain followers on social media are expected to maintain activity to retain their audience.

To make the enforcement of influence claims even more explicit, strings now serve not only as indicators of influence flow but as tangible “obligations” among attendees. If someone’s placard shows a connection to a prominent commenter or amplifier, they have a right to expect some form of engagement back, and the officials monitor these connections. For instance, if Goldhaber’s main amplifier stops engaging or fails to respond to someone in their network, they receive a warning: their influence is conditional upon reciprocating attention to their followers or contributors.

The role of the officials expands. They now monitor each participant’s influence metrics in real-time, responding to every interaction, engagement, and reactions. These officials wear special uniforms marked with symbols indicating their roles: some are “Trend Spotters,” others are “Engagement Boosters,” and some are “Content Curators.” They circulate throughout the room, observing attendees’ activities and recalibrating the flow of influence based on what they detect.

Every few minutes, the Trend Spotters scan the room to find “hot zones,” which are clusters of people who are engaged with an idea or reacting intensely to a particular comment or aspect of Goldhaber’s talk. When they find a hot zone, they immediately place large, visible “signal beacons” above that group, directing influence flows toward it. The Trend Spotters then alert the Engagement Boosters, who direct the participants in other parts of the room to take notice of these beacons by offering them influence tokens as rewards for tuning in to what’s happening in the hot zone. This way, the algorithmic officials prompt waves of influence flows in the room.

The officials never rest, and introduce a new special feature. Periodically, they select an attendee at random, someone who has had minimal influence or attention thus far. They assign a few Engagement Boosters to this person and begin pushing their ideas or reactions to the forefront, creating an “artificial surge” in influence. Observers are now drawn to this previously low-profile attendee, who experiences an influence boost based solely on the officials’ intervention.

Attendees respond to these influence credit, some engaging immediately and binding themselves to the new attendees. However, others, a group of “Influence Skeptics,” resist and actively choose to avoid engaging with what the officials push towards them. The officials respond by subtly downgrading these attendees’ influence scores. But a few skeptics, through sheer persistence and unique engagement strategies, manage to attract their own following of similarly skeptical attendees, thereby creating a counter-current of influence within the room.

The officials continue to expand their capacity to issue new forms of influence claims, now use a complex system of colored tokens to categorize the types of engagement happening. Each color represents a different “interest profile,” like “Intellectual Curiosity,” “Entertainment,” “Controversy,” and “Affirmation.” When someone reacts to a comment, they receive a token in the color associated with that engagement type. Over time, each participant builds a unique stack of colored tokens that represents their “engagement profile.”

The algorithmic officials use these profiles to direct each participant to specific zones or types of content in the room that best match their engagement style. For example, an attendee with many “Controversy” tokens will be drawn to heated debates, while someone with mostly “Affirmation” tokens will be directed to high-engagement amplifiers offering positive feedback.

New role types arise. “Commentators” are now given freedom to circulate without any specific seating, like mobile observers weaving between groups. They don’t just engage directly with Goldhaber; instead, they observe interactions among attendees and leave “meta-comments” on others’ engagement. They gain influence tokens based on the number of observers who echo or amplify their commentary, and when a meta-comment itself gains traction, it’s elevated by the officials and projected on large screens for everyone to see.

Goldhaber now finds himself increasingly marginalized by the frenetic swirl of influence around him. His carefully prepared lecture notes seem almost quaint as they fade into the background of a room saturated with rapid, algorithm-driven exchanges. In some cases, the officials direct him to respond to attendees with high influence scores to maintain his relevance, while also encouraging him to echo trending reactions in his lecture to keep pace with what’s capturing the room’s engagement.

Determined not to fade completely into obscurity, Goldhaber decides, with a mix of curiosity, irony, and a touch of desperation, to participate in the very dynamics that have overtaken his lecture. He sets aside his notes, steps down from the podium, and attempts to perform a short, trending TikTok dance that he's seen circulating among younger audiences.

He raises his hands and starts moving in sync with the beat of an imaginary track, executing the precise gestures of the dance as best he can manage. The engagement signals spike as the Trend Spotters, captivated by the incongruity of Goldhaber himself become enthralled to the circulating claim token, swarm around him and activate a massive signal beacon above his head, drawing attendees from all corners of the room.

As his dance garners laughter, applause, and a flurry of colored tokens from attendees, Goldhaber feels both elated and vaguely melancholic. He is back in the limelight, yet acutely aware that his speech has become posterized: a shadow substance reflecting the new mechanics of influence he helped to define. With a final flourish, he completes the dance, catching his breath as he looks around the room, now a vast, self-sustaining influence ecosystem in which everyone, himself included, is caught in the ever-shifting currents of social capitalism. The crowd erupts in cheers and tokens fly.

As Goldhaber’s dance unfolds to the rhythm of the crowd’s demand for more, placards light up around the room with sharp spikes of engagement. Trend Spotters, hastily scribbling signals of virality, create trails of flashing lights around him, a feverish beacon drawing viewers from every corner of the auditorium. The engagement levels are surging so high that for a moment, it appears as though Goldhaber’s influence is unstoppable, riding the wave of “likes” and “shares” as if he were at the crest of a digital influence bubble.

But bubbles must burst. As viewers swarm to witness the spectacle, smaller placards begin blinking with warning signals: “Content Overload Detected” and “Attention Saturation Imminent.” The Trend Spotters and Signal Managers are now operating with a heightened intensity, unable to keep up with the sheer volume. Some in the crowd grow disenchanted, noting that the quality of the performance has plateaued, even dipping slightly as Goldhaber strains to keep the energy high.

In the corners of the room, figures in dark suits and glasses – the “Cancellers” -- begin to circulate, ominously holding placards reading “Inauthentic Engagement Detected” and “Offensive Content Alert.” They signal that the tipping point is near. Suddenly, a cascade effect unfolds as viewers lower their placards, retracting their engagement. Some even turn away, placing their placards down, signaling their disinterest. The energy in the room sharply contracts, and Goldhaber’s momentary influence bubble collapses as quickly as it formed, his once-thriving crowd shrinking back to a fraction of its size.

The crowd’s disengagement ripples through the hall, with placards now displaying “Credibility Drop” and “Influence Bust.” The Trend Spotters quickly disperse, abandoning Goldhaber as they sense the collapse. Goldhaber, exhausted, finally lowers his arms, watching as his influence bubble pops and the swarm disperses. The bright signal beacons, once pulsating with the allure of high engagement, fade to a dim glow, flickering off one by one, like streetlights shutting down in an emptying city.

He stands alone in the center of the stage, surrounded by fallen placards and darkened signals, facing the reality of influence’s inherently risky nature. As Goldhaber’s influence bubble collapses, the contraction of influence claims ripples beyond the immediate vicinity of the lecture hall. First, his immediate circle of commentators and Trend Spotters -- those who had been signaling and amplifying his influence -- feel the sting. Their placards, once lit with association to his temporarily thriving engagement, now flash in erratic warning signals: “Connection Risk,” “Visibility Loss,” “Influence Devaluation.” Followers who had relied on Goldhaber for their own influence experience an immediate downturn as the value of his influence fades. Some scramble to reallocate their influence, hurriedly turning to new figures in the room, hoping to ride on their waves instead, but the sudden glut of influence withdrawal only dilutes their value further.

The “Cancellers” who initiated the bust move on to others in Goldhaber’s network, casting their cancellation alerts like nets over a broader circle of affiliated influencers, each placard representing a tightening of influence liquidity. Those previously uplifted by their ties to Goldhaber see their reach contract, their signals of influence dimming as the contagion spreads. Influencers who once rode high on the indirect boost from his network find their metrics taking hits: follower counts stagnate, likes and shares dwindle, and engagement placards that had once promised steady flow begin flashing in red, warning of “Negative Credibility Impact” and “Secondary Influence Bust.”

The Cancellers reach extends further, rippling through the crowd like a shockwave. Influencers who had only tangential associations with Goldhaber suddenly feel the tremors; their placards flicker uncertainly as attention metrics plummet, and the influence-credit owed to them dwindles. Some look on in alarm as their carefully built “follower connections” disintegrate before their eyes, little strings and markers snapping under the strain. Content creators, who once thrived on the steady flow of engagement, now see their metrics crash, as attendees, caught in the frenzy of this influence “market contraction,” pull back their influence, clutching their placards closer, unwilling to risk association in this shaky climate.

Meanwhile, the platform itself responds swiftly. Its managers deploy emergency “engagement incentives.” They raise the visibility of any untouched creators, attempting to revive the ebbing flow of influence and stabilize the system. Colored lights flash across the ceiling, illuminating new figures in the crowd, beckoning the audience toward fresh, untainted sources of clout. "New Discoveries!” banners unfurl, drawing the wavering crowd’s attention in an orchestrated attempt to reinflate demand for influence, to “redistribute” attention where it’s least vulnerable.

But these tactics have mixed results. Some attendees hesitantly engage with new faces, and a few fledgling accounts eagerly soak up the sudden rush of interest, like young plants after a drought. Yet, many in the audience remain wary, clutching their “engagement tokens” close, as though mistrustful of this next wave. A haze of uncertainty lingers, and beneath the grand display, a current of suspicion ripples through the network, creating a sense that influence, once so readily bestowed and exchanged, is no longer a reliable measure of value.

In the aftermath, the crowd, once a unified web of vibrant exchange, has fractured into cautious clusters. Only a few pockets of influence remain as strongholds, while others resemble an influence “wasteland,” void of the willingness to sacrifice control over their placard space to others that once powered their allure. The platform, in its effort to restore order, has succeeded in drawing some eyes back to the stage, but the crowd has fundamentally changed: more cautious, more skeptical, less willing to give up control over their placard spaces so freely.

As the dust of the cancellation settles, the platform initiates an “austerity protocol” to stabilize the influence ecosystem. Suddenly, the opulent display of neon-lit banners and engagement-flashing placards dims, and a hush falls over the room as new restrictions roll out. Strings connecting influencers to attendees tighten; gone are the frivolous, easily won interactions. Engagement tokens are now harder to come by, requiring attendees to confirm their “influence investments” with formal pledges of allegiance, signing miniature contracts that bind them to a set number of interactions over time. A new heavy rope ties them together, with the mysterious label “Substack.”

The austerity measures impose a stricter regime of metrics and access. Influence is no longer freely allocated to the newly trendy or the whimsically popular; only those influencers with sustained, proven “engagement histories” retain their placements on the stage. The Trend Spotters, once buzzing freely between influencers, sparking quick bursts of virality, are now heavily regulated, their actions restrained to only those participants deemed “engagement-viable” by the platform officials’ calculations. This austerity-driven pruning of influence redistributes influence but only to those who can meet the new rigorous standards.

In one corner, a long-established influencer tentatively raises her voice, knowing that every post, every comment must carry more weight to hold her followers’ credit. Meanwhile, among the attendees, there is a sense of renewed gravity to the act of engagement. Tokens are given sparingly, each one representing a commitment: a real “debt” they owe to the influencer. Do I really want the whole world to know I follow this person, that I give them influence? A few brave newcomers see this as an opportunity to demonstrate loyalty; they invest their tokens in the established figures, hedging their “engagement debt” in safer, historically reliable accounts. The crowd itself grows quieter but more focused, as followers carefully choose where to place their limited resources, driving up the value of each connection and “like” given.

As this austerity continues, a slow but undeniable resurgence begins. The scarcity and concentration of influence lead attendees to value their engagements more deeply. Content creators who survive this new landscape emerge stronger, backed by more deliberate, committed followings that no longer fluctuate with fleeting trends. The platform regains some control, acting like a central authority managing the supply of influence through oscillating between discipline and elasticity.

By night’s end, the room hums with a new rhythm. For now, stability has been restored, though the cost is clear in the diminished energy and tempered expectations of all those involved. The Trend Spotters begin to awaken, and the cycle begins anew.